THE HUMAN SPRING APPROACH TO

THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME

by Dr James Stoxen DC., FSSEMM (hon) FWSSEM

SAMPLE CHAPTER

CHAPTER I

An injury initiates a process of recovery.

More important, it initiates a process of discovery.

—Unknown

If you have headaches, neck pain, upper back pain, or shoulder pain, you might have thoracic outlet syndrome.

Some people who haven’t been to a doctor for a proper diagnosis call it by the slang terms of office syndrome, cell phone syndrome, or smartphone syndrome. After thoracic outlet syndrome has taken over their lives, they prefer to call it by its initials, TOS, for short.

The condition can be caused by compression of more than one area of the neck, upper back, rib cage, the shoulder, and the nerves in the surrounding area. That is why it produces a variety of symptoms.

These atypical symptoms are the result of persistent compression of nerves, arteries, and veins traveling through the thoracic outlet and tunnel and also the twisting of the body parts that keep your entire upper body, neck, and head locking in chronic pain.

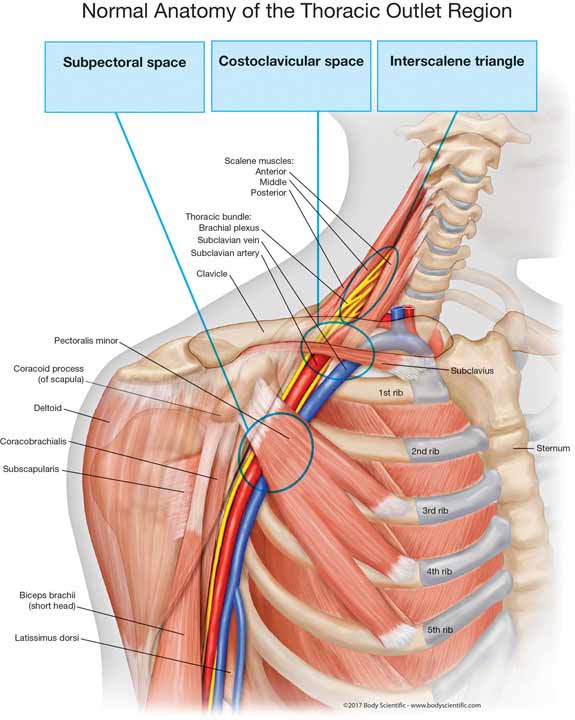

The Thoracic Outlet or Tunnel

The thoracic outlet, inlet, or compartment is a tunnel located under the shoulder and over the rib cage, where the artery, vein, and nerves pass from the chest and neck area into the arm and hand. I call the thoracic tunnel the passageway where the artery, vein, and nerves pass from the outlet over the first rib, over the rib cage, under the collarbone, and under the pectoralis minor into the arm.

It affects approximately 8 percent of the population, with women about four times more likely to develop a neurogenic TOS.

It is one of the most underrated, overlooked, and misdiagnosed conditions and proves difficult to manage. Medical professionals appreciate that it is probably the most important peripheral nerve compression in the upper extremity (1).

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is one of the most controversial subjects in medicine (1).

History

TOS was first described by Sir Ashley Cooper in 1821 (2). Then, in 1861, Richard Holmes Coote at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, England, performed one of first surgical procedures, the removal (resection) of a cervical rib, for what came to be termed arterial TOS (3).

Thoracic outlet syndrome was coined in 1956 by R. M. Peet et al. to describe the impacts of compression of the blood vessels and nerves, called the neurovascular bundle in the thoracic outlet or tunnel (4).

The compression can be in one area or in a combination of three possible areas within the tunnel. I usually find the compression is in all three areas.

Unfortunately, this name has been used since then as a catchall to include myriad symptoms relating to compression at any point along the thoracic outlet passageway. Many doctors believe there should be sub names or titles relating to specific areas of compression to better describe the thoracic outlet syndrome patients have (5).

Thoracic outlet syndrome has been called many names, as mentioned previously, including office syndrome, cell phone shoulder, and cell, mobile or smartphone syndrome. Doctors have an even more confusing list of names for thoracic outlet syndrome, such as thoracic outlet disorder, arterial TOS, neurogenic TOS, arterial thoracic outlet syndrome, bilateral thoracic outlet syndrome, cervical rib syndrome, cervicobrachial neuralgia, compressive neuropathy, costoclavicular syndrome, disputed neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome, double crush syndrome, effort thrombosis, first rib syndrome, hyperabduction syndrome, inflammation of the brachial plexus, neurogenic pectoralis minor syndrome (NPMS), neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (NTOS), neurological thoracic exit syndrome, Paget-Schroetter syndrome, peripheral nerve compression, scalenus anticus syndrome, spontaneous subclavian vein (“effort”) thrombosis, subcoracoid brachial plexus compression, superior thoracic outlet syndrome, symptomatic thoracic outlet syndrome, thoracic outlet compression, triple crush, venous compression syndrome, and venous thoracic outlet syndrome.

What I Learned from Lecturing to More Than 50,000 Doctors around the World.

I have been invited to give presentations to doctors and scientists about the human spring application to aging, sports, etc., at more than 50 medical conferences. I have lectured on the human spring approach to the earliest detection, intervention, and prevention of thoracic outlet syndrome at these fifteen medical conferences.

- Keynote Presentation:The World Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Conference, Istanbul, Turkey 2018

- Keynote Presentation:The 4th International Conference on Sports Medicine, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK 2018

- Keynote Presentation: The 18th Global Neuroscience Conference, Tokyo, Japan 2018

- Keynote Presentation: The 2nd International Conference on Surgery and Medicine, Dubai, UAE 2018

- Keynote Presentation: The 2ndGlobal Congress on Medical & Clinical Case Reports, Dubai, UAE 2018

- Plenary Presentation: The World Congress in Sports and Exercise Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017

- Plenary Presentation: The Global Orthopedicians Annual Meeting, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017

- Plenary Presentation: The 9th Thailand Congress on Anti-aging and Aesthetic Medicine 2017

- Plenary Presentation: The Florida Chiropractic Physicians Association Conference, USA 2016

- Plenary Presentation: The World Congress in Sports and Exercise Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015

- Plenary Presentation: The World Congress in Sports and Exercise Medicine, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2015

- Plenary Presentation: The Florida Chiropractic Physicians Association Conference, Orlando, Florida, USA 2015

- Plenary Presentation: The Florida Chiropractic Physicians Association CE Seminar, Orlando, Florida, USA 2013

- Plenary Presentation: The ICAs Symposium on Natural Fitness Event: “Arnold Classic” 2005

- Plenary Presentation: The 12th Annual World Congress On Anti-Aging Medicine, Las Vegas, Nevada USA 2004

I have taught thousands of doctors the new human spring approach and how it applies to the thoracic outlet syndrome. I teach them new ways to examine for it and treat it successfully without surgery. I also teach doctors how to prevent it. I will never forget the lecture I gave at the Royal College of Surgeons in England.

What you might not realize is that most of these doctors don’t understand basic anatomy, biomechanics, or engineering of the thoracic outlet and tunnel.

You would think that with years of schooling, they would know basic anatomy down cold. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Studies prove it!

According to an article published in the Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England, author Ben Turney stated For 30 years, there has been a decrease in the undergraduate knowledge of anatomy in the surgical community (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11)

He goes on to say, “These studies report reductions in allocated time, teaching staff and dissection in most anatomy courses. It is very difficult to assess objectively whether this reduction in anatomy teaching has been excessive. However, the few studies that have been conducted suggest that the knowledge of the qualifying doctor is now below an acceptable level”. (12–14).

Here is an example of how confusion with basic anatomy can lead to a huge problem for you. The usual surgical approach is to remove three muscles: the anterior scalene muscle, the middle scalene muscle, and sometimes the pectoralis minor muscle. Because these muscles are contracting against the first rib, raising it into the outlet, they cut that too.

Here is an extremely important lesson in anatomy you will learn in later chapters:

- There are three muscles (anterior scalene muscle, middle scalene muscle, posterior scalene muscle) that directly pull the first and second ribs into the outlet from the top.

- There are six muscles (subclavius muscle, pectoralis minor muscle, biceps short head muscle, coracobrachialis muscle, lower trapezius, and latissimus dorsi muscle) that drag the shoulder girdle down into the outlet from below.

- There is one muscle (anterior neck muscles,) which indirectly contributes to the overall compression of the neck.

That makes a total of nine muscles that directly contribute to the compression of the outlet, and one muscle that indirectly contributes to the compression of the outlet and a total of 10 muscles that either directly or indirectly contribute to the compression of the thoracic outlet.

What if your doctor or therapist only focused on three muscles (the anterior scalene muscle, the middle scalene muscle, and the pectoralis minor muscle), thinking this was all that’s needed to decompress your thoracic outlet? Why do surgeons only surgically remove three muscles, when according to every anatomy book there are nine muscles that directly compress the outlet?

Surgeons only remove these three muscles because if they cut out any more, you wouldn’t be able to do the simple activities of everyday life.

They know removing only these three muscles cannot completely decompress your thoracic outlet. Therefore, they know they cannot bring you 100 percent relief, and they aren’t expecting you to be pain free after surgery either.

You might wonder . . . If doctors don’t understand the engineering of the thoracic outlet, how can I understand it? Don’t worry, I will teach you, in Chapter 2, “A Painful Misunderstanding of Human Engineering,” in simple terms exactly how your body’s marvel of spring engineering works.

This chapter has full-color, custom illustrations of the anatomy that are well demarcated. When you look at these illustrations, you’re going to “get it.”

In this book, I am going to teach you self-help massage techniques to self-treat all 10 muscles to ensure you get 100 percent of the pressure off your thoracic outlet. We need to learn about the anatomy and biomechanics in the next three chapters to understand how to do it.

The thoracic outlet is designed with spring engineering to allow for the safe passage of blood vessels and nerves through a series of three passageways, which I refer to as the thoracic tunnel.

The thoracic outlet is designed with spring engineering to allow for the safe passage of blood vessels and nerves through a series of three passageways, which I refer to as the thoracic tunnel.

The three passageways are named—

- scalene triangle

- costoclavicular space

- subcoracoidspace

Scalene Triangle

The scalene triangle is formed by the anterior scalene muscle, making up the front of the triangle; the middle scalene muscle, making up the back of the triangle; and the first rib, that represents the foundation of the triangle.

Costoclavicular Space

The costoclavicular space is the next passageway that the bundle of blood vessels and nerves traverses. It is formed by the first, second, and third ribs at the foundation; the anterior scalene muscle in the front; and the subclavian muscle and clavicle or collarbone at the roof.

Subcoracoid Space

The subcoracoid space is the third passageway that the bundle of two blood vessels and nerves must travel through before entering the arm. The bundle travels under the coracoid process, at the roof, and pectoralis minor muscle, and in front of the ribs in the back.

Blood Vessels and Nerves Passing through the Outlet/Tunnel

The neurovascular bundle travels through these three passageways and consist of the subclavian artery. The subclavian vein and a group of nerves, called the brachial plexus, branch out between the vertebrae in the neck. Subclavian means under the collarbone.

The subclavian artery supplies blood to the arm. If it’s compressed, blood can’t get to your arm to supply the cells with oxygen and nutrients. Therefore, you have numbness and weakness in the whole arm. Sometimes the skin is a pale color, and in some cases, this can cause a blood clot (embolus) that could threaten the life of your arm.

The subclavian vein removes the blood or drains the blood. If it’s compressed, your blood will not be able to drain from the arm. If the drainage of the blood is blocked or compromised, the hand and arm will begin to swell. You might see one arm and hand is puffy or fatter than the other. Commonly, the swelling is enough that rings don’t fit or are too tight on the fingers.

The nerve bundle supplies feeling to the arm. If it’s pinched, you’ll have a lack of feeling or pins and needles, called paresthesia, in the arm. You might also feel shooting pain or deep, boring, achy pain in your arm. This usually begins in the ring finger and pinky finger. When the first rib becomes more elevated, it compresses nerves higher in the plexus. This leads to the symptoms of radiating numbness, tingling, or pain into the middle finger, index finger, and then the thumb.

If the compression affects the deeper portions of the nerve, where the nerves control the contraction of muscles of the arm and hand, you might feel weakness that could lead to you frequently dropping items, like utensils or cups. You might also have a difficult time opening jars. In severe cases, the hand muscles could waste away.

What Is the Cause of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome?

The Mayo Clinic, the Cleveland Clinic, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, plus the top-10 ranked hospitals for neurology and neurosurgery tell us that compression is what leads to thoracic outlet syndrome.

Mayo Clinic

Thoracic outlet syndrome is a group of disorders that occur when blood vessels or nerves in the space between your collarbone and your first rib (thoracic outlet) are compressed (15).

Cleveland Clinic

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a term used to describe a group of disorders that occur when there is compression, injury, or irritation of the nerves and/or blood vessels (arteries and veins) in the lower neck and upper chest area (16).

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

TOS is an umbrella term that encompasses three related syndromes that involve compression of the nerves, arteries, and veins in the lower neck and upper chest area and cause pain in the arm, shoulder, and neck.

Most doctors agree that TOS is caused by compression of the brachial plexus or subclavian vessels as they pass through narrow passageways leading from the base of the neck to the armpit and arm, but there is considerable disagreement about its diagnosis and treatment (17).

In Chapter 5, I agree that thoracic outlet syndrome is caused by a compression of the blood vessels and nerves as they pass from the chest and neck into the arm.

If your artery is compressed long enough . . . you could end up losing your limb to amputation.

If you have compression of the vein too long or too deep, a clot could form, releasing as an embolus, causing a stroke in your lung. If you think you have a compressed vein or artery, you have to quickly get treatment for your thoracic outlet syndrome.

If the cause of TOS is compression, why can’t we reverse the compression in the head, neck, and shoulder area without surgery? Because the approaches most doctors use is ineffective at reducing the cause of the compression. In fact, most of them don’t even know what causes it.

Four Types of TOS

There are four types of thoracic outlet syndromes.

For our practical purposes, if the outlet is compressed, the blood vessels and nerves are all somewhat compressed. However, for surgeons this is more important.

- Neurogenic TOS—compression of the nerves in the bundle

- Venous TOS—compression of the vein of the bundle

- Arterial TOS—compression of the artery of the bundle

- Disputed TOS—it is disputed that there is a thoracic outlet syndrome symptom pattern, but the exact cause cannot be determined. Now, what you really want to know is what is causing the compression and how to reverse it so you can get relief.

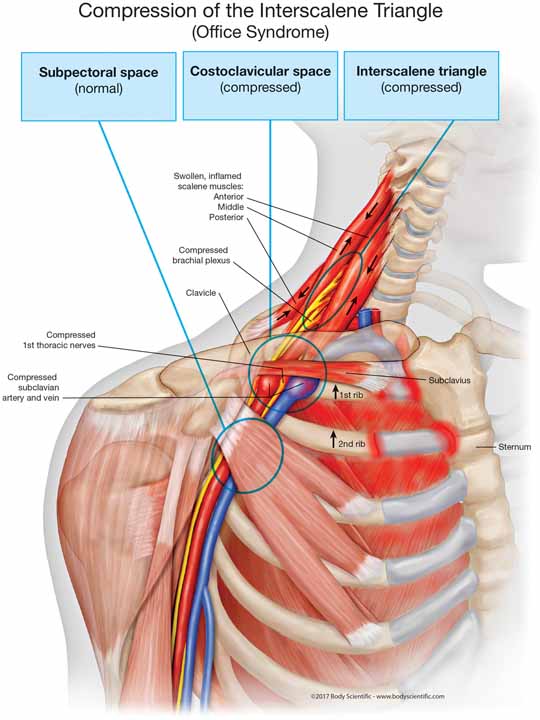

Your Bad Habit Can Predict the Area of Compression of the Thoracic Outlet.

A more useful classification of thoracic outlet syndrome I devised classifies the condition according to the cause of the compression.

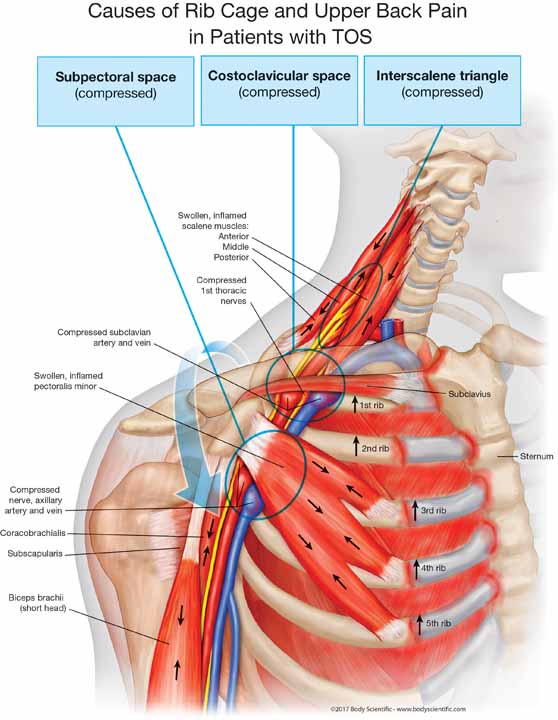

For example, if you spend a lot of time leaning back on the couch, in the car with the seat back, leaning to the side at your desk, etc., you are essentially dangling your 9–12-pound head from your scalene muscles. In this case, you will be more likely to have compression in the interscalene triangle than the costoclavicular space or subcoracoid space. The illustration above is an example of what would be going on inside your neck and shoulder with these bad habits.

For example, if you spend a lot of time leaning back on the couch, in the car with the seat back, leaning to the side at your desk, etc., you are essentially dangling your 9–12-pound head from your scalene muscles. In this case, you will be more likely to have compression in the interscalene triangle than the costoclavicular space or subcoracoid space. The illustration above is an example of what would be going on inside your neck and shoulder with these bad habits.

If you spend a lot of time working with your hands above your head, working with the mouse and keyboard at the computer, and talking and texting on your smartphone, then you are more likely to have compression of the costoclavicular space or subcoracoid space. The illustration above is an example of what would be going on inside your chest, shoulder, and arm with these bad habits.

If you lean, talking, texting, typing, browsing, working overhead, and had an accident or a work or sports injury, you might have compression in all three areas, making your case more difficult and time-consuming to reverse. The illustration above is an example of what would be going on inside your chest, shoulder, and arm with all these bad habits.

Because I classify TOS this way, I know what area to concentrate on for treatment, and you will know what bad habits to focus on removing to keep the condition from returning.

Other Symptoms of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome in the Surrounding Area

There are many more symptoms associated with the syndrome than just those coming from the compression of the neurovascular bundle.

Because the muscle spasms twist your skull, neck, shoulders, upper back, and rib cage, there are headaches, neck pain, and stiff neck, along with upper back pain, shoulder pain, and even shortness of breath in some instances.

There are also symptoms that come from muscle spasms twisting and compressing your neck and upper back, twisting and locking your ribs, and depressing your shoulder girdle.

As the muscular compression of the neck, upper back, shoulders, and chest can lead to narrowing of the thoracic outlet, you might initially feel slight numbness and tingling of the fingertips, then more progressive numbness and weakness in the hands when gripping objects, such as opening a jar, and you might even start dropping items.

The symptoms can be in one arm or in both arms. In fact, if the symptoms are in both arms, it’s more likely thoracic outlet syndrome, making it easier to diagnose. If you have numbness in both arms, it is more likely to be thoracic outlet syndrome than other extremely rare conditions that cause numbness or radiating symptoms in both upper extremities.

In extreme cases, you might see wasting of the muscles of the hand and arm, discoloration of the hand, cold fingers and hands, a lack of color in the hand, and even pain and swelling in the arm and hand, possibly due to blood clots.

Neck Compression Symptoms

These symptoms of neck compression include stiff neck, neck pain, and headaches (severe headaches are often misdiagnosed as a migraine), and even radiating numbness in the cheek, earlobe, shoulder, and outer arm. Patients can also have vertigo and dizziness.

Shoulder Compression Symptoms

These symptoms can be similar to a rotator cuff syndrome, consisting of a stiff and painful shoulder, weakness in the shoulder, pain below the collarbone, and sharp, burning pain between the shoulder blades.

- The upper back and shoulder pain is most likely caused by an anterior, middle, and posterior scalene muscle spasm, yanking your first and second ribs up, twisting the rib joints where they attach at the breast bone and upper spine.

- The mid-back and shoulder pain is most likely caused by a pectoralis minor muscle spasm, yanking the third, fourth, and fifth ribs up, causing pain between the shoulder blades in the mid-upper back.

Upper Back and Chest Compression Symptoms

These symptoms are related to the misalignment caused by the muscles that attach to the ribs, causing compression of the rib cage.

- The upper back and shoulder pain is most likely caused by an anterior, middle, and posterior scalene muscle spasm, yanking your first and second ribs up, twisting the rib joints where they attach at the breast bone and upper spine.

- The mid-back and shoulder pain is most likely caused by a pectoralis minor muscle spasm, yanking the third, fourth, and fifth ribs up, causing pain between the shoulder blades in the mid-upper back. There are many other muscles that can spasm and compress the chest, leading to anything from tightness in the chest to difficulty getting a full breath, difficulty breathing, and even crushing chest pain, making you feel like you are having a heart attack.

Nerve Compression Symptoms

In more advanced cases, weakness can occur in the hand and fingers, causing a loss of hand dexterity and/or a numb hand or arm. As it progresses, there can be muscle weakness and atrophy and an inability to use the arm, without any findings in the neck to suggest paralysis.

Vein Compression Signs and Symptoms

If the shoulder, including the collarbone or other structures, compresses the outlet, compressing the vein, you might note swelling of the arm and discomfort in the arm and hand related to the swelling. Commonly, people will notice their rings don’t fit due to swollen fingers.

Artery Compression Symptoms

If the shoulder and collarbone compress the artery, you might feel symptoms such as coldness, white skin or pallor, and weakness in the arm and hand with exercise. Patients suffering from compression of the artery or vein can have pain and numbness distributed across the shoulder, arm, and hand that does not conform to the typical pinched-nerve pattern. Your hand might be cool to the touch and can be pale or bright red. Arterial compression leads to a lack of blood flow in the arm, which can feel worse when it’s cold outside.

Why is Thoracic Outlet Syndrome So Difficult for Doctors to Manage?

Thoracic outlet syndrome is notoriously difficult to manage, both conservatively and surgically. According to a group of doctors in the “Reporting Standards of the Society for Vascular Surgery for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Executive Summary,” NTOS is often difficult to manage, because of

- nonspecific symptoms,

- poorly understood pathophysiologic mechanisms (the cause),

- limited applicability of “objective” testing procedures,

- potential overlap with other clinical disorders, and

- an absence of well-defined, generally accepted, or consistently applied criteria for diagnosis and treatment.

- Thoracic outlet syndrome has nonspecific symptoms because of three reasons.

The muscles that cause compression on the outlet attach at the neck, shoulders, rib cage, arms, and head. So, you can have pain in all of these areas.

Example 1: If there is a lot of tension in the scalene muscles, because they attach at the neck and the first two ribs, you can have neck pain from the muscles pulling down on the neck. You can have upper back/shoulder pain from the muscles pulling against the upper ribs. You can have numbness in the arm when the scalene muscle is pulling the rib up into the outlet.

Example 2: If there is a lot of tension in the pectoralis minor muscle, because it attaches at the front of the shoulder and the third, fourth, and fifth ribs in the front, you can have shoulder pain when the shoulder is dragged down. When the shoulder is dragged down, it pulls on the lower neck. When the shoulder is dragged down, it can put pressure on the blood vessels leading to a blue tone, red tone, or gray tone of the arm from the blood not escaping from the arm or when blood is blocked in the arm. You can experience numbness, tingling, or weakness in the arm and hand, because the nerve can become compressed. Because the muscle is pulling on the ribs in the front, this can cause a shift in the ribs where they attach in the font and the back by the spine. So, you can have shortness of breath, pain between the shoulder blades, chest pain, and a feeling like you are having a heart attack.

- Thoracic outlet syndrome has a poorly understood pathophysiologic mechanisms (the cause).

The committee of doctors had a difficult time determining the cause, but what makes this easier is that compression is the cause of thoracic outlet syndrome. The only way you can have any body part compressed is when muscles contract. Therefore, muscle tension is the cause of TOS. That is why the usual approach to treatment is to cut the muscles out.

- Thoracic outlet syndrome has a limited applicability of “objective” testing procedures.

Some doctors need to get a scan of the body, or it doesn’t exist. They are used to being able to take a picture of everything to make their job easier. If they do a scan, they don’t have to be so good at an exam. I don’t order a lot of tests, and people get diagnosed correctly and with treatment they get better. Unless professionals are preparing a legal case, they should be able to diagnose thoracic outlet syndrome with a simple examination.

- There is a potential overlap with other clinical disorders.

It is true that there are often several compression syndromes going on at the same time with thoracic outlet syndrome. If I suspect carpal tunnel syndrome, a shoulder rotator cuff strain, and thoracic outlet syndrome, I would work on all three at the same time.

- There is an absence of well-defined, generally accepted, or consistently applied criteria for diagnosis and treatment.

There are 10 diagnostic tests that can be ordered by doctors to help diagnose thoracic outlet syndrome. However, doctors state that not one of these tests is the gold standard to diagnose thoracic outlet syndrome. None of these tests can determine the cause of your thoracic outlet syndrome.

There were 16 different treatments discussed in the literature for treating thoracic outlet syndrome. Not one of these treatments by themselves can effectively reverse the cause of the compression of the outlet. It takes a specific combination of treatments and recommendations to fully address the cause of TOS. Also, there are specific criteria for each treatment to ensure the TOS is corrected to maximum medical improvement, so it will not return.

Examination and Treatment Are Based on a Flawed Model of Biomechanics

The success rate for nonsurgical treatment is not good for thoracic outlet syndrome. There are a lot of reasons for this, which I will explain in the book.

What if I were to tell you that all treatments and recommendations made by doctors today are based on an outdated medical model about how the body moves, absorbs impacts, and recycles energy, and, most important, how it provides for the safe passage of blood vessels and nerves?

After reading this book, you will shake your head, wondering how these doctors expect to get any improvement because this 340-year-old, outdated model of human movement doesn’t even abide by the laws of physics or nature. In my opinion, if you see improvement from the standard-of-care treatments mentioned above, it is just a fluke.

If you don’t know why you’re suffering, and your doctor doesn’t really know why you’re suffering, he could tell you anything and you would likely believe him.

Knowing doctors, this is not a good strategy. You have to know how your body works, so you can make wise decisions on what is right for you.

Don’t worry—it’s all here for you. After reading this book, you will know more about the human body, how it works, how it breaks down and compresses into a chronic state of suffering than 99 percent of the doctors in your city. You will also learn how to reverse these changes and get back to enjoying life, pain free and fully functional.

Also, once you read the next two chapters, I guarantee you will never let any doctor examine or treat you the same way again.

Let’s spring into the spring chapter.

CHAPTER 1 – REFERENCES

- Atasoy E. Thoracic outlet compression syndrome. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:265–303 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8614579

- Cooper, B. Travers (Eds.), Surgical essays, Longman, London (1821), p. 128

- Coote H. Pressure on the axillary vessels and nerves by an exostosis from a cervical rib; interference with the circulation of the arm; removal of the rib and exostosis, recovery. Med Times Gaz. 1861;2:108.

- Roos DB. Historical perspectives and anatomic considerations. thoracic outlet syndrome. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;8:183–9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8672572

- Ranney D. Thoracic outlet: an anatomical redefinition that makes clinical sense. Clin Anat. 1996;9(1):50-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8838281

- Turney BW1. Anatomy in a modern medical curriculum. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007 Mar;89(2):104-7. Full Free http://publishing.rcseng.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1308/003588407X168244

- Kaufman MH. Anatomy training for surgeons–a personal viewpoint. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1997 Aug;42(4):215-6. Abstract https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9276550

- Shaffer K1. Teaching anatomy in the digital world. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 23;351(13):1279-81. Abstract https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15385652

- Older J1. Anatomy: a must for teaching the next generation Surgeon. 2004 Apr;2(2):79-90. Abstract https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15568432

- Anon. The rise and fall of anatomy. BMJ Career Focus. 2005;330:255–6.

- Heylings DJ1. Anatomy 1999-2000: the curriculum, who teaches it and how? Med Educ. 2002 Aug;36(8):702-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12191052

- Waterston SW1, Stewart IJ. Survey of clinicians’ attitudes to the anatomical teaching and knowledge of medical students. Clin Anat. 2005 Jul;18(5):380-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15971223

- McKeown PP1, Heylings DJ, Stevenson M, McKelvey KJ, Nixon JR, McCluskey DR. The impact of curricular change on medical students’ knowledge of anatomy. Med Educ. 2003 Nov;37(11):954-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14629407

- Prince KJ1, Scherpbier AJ, van Mameren H, Drukker J, van der Vleuten CP. Do students have sufficient knowledge of clinical anatomy? Med Educ. 2005 Mar;39(3):326-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15733169

- Mayo Clinic WebSite http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/thoracic-outlet-syndrome/home/ovc-20237878

- Cleveland Clinic https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/thoracic-outlet-syndrome

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) web site https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Thoracic-Outlet-Syndrome-Information-Page

Meet Dr James Stoxen DC., FSSEMM (hon)

President, Team Doctors® Masters Academy

www.drstoxen.com

Dr Stoxen’s Curriculum Vitae

Stay connected to our thoracic outlet syndrome social media sites

1.1k

Members

READ THESE CHAPTERS OF DR STOXENS BOOK FREE HERE!

ARTICLE CATEGORIES

- Testimonials (13)

- Success Stories (13)

- Failed TOS Surgery (1)

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (11)

- Compartment Syndrome – Forearm (5)

- Shoulder Replacement Surgery (1)

- Cervical Discectomy (1)

- Cervical Fusion Surgery (1)

- What is TOS? (3)

- Thoracic Outlet Anatomy (1)

- Thoracic Outlet Engineering (1)

- Causes Of TOS (6)

- The TOS Examination (1)

- Diagnostic Tests for TOS (1)

- What Mimics TOS? (1)

- Paget-Schroetter Syndrome (2)

- TOS Surgery (2)

- Posture Tips (1)

- Self Treatment (1)

- What doesn’t work and why? (1)

- What works and why? (1)

- Stretches for TOS (1)

- Exercises for TOS (1)

- Surgery for TOS (1)

- Case Studies (2)

- Chapter Reviews (10)

- Uncategorized (16)

VIDEO TUTORIALS

Subscribe to our newsletter

Team Doctors® Master’s Academy

Professional Development Courses

Launching January 1, 2022!

Team Doctors® Master’s Academy

Patient Self-Care Workshops

Launching January 1, 2022!