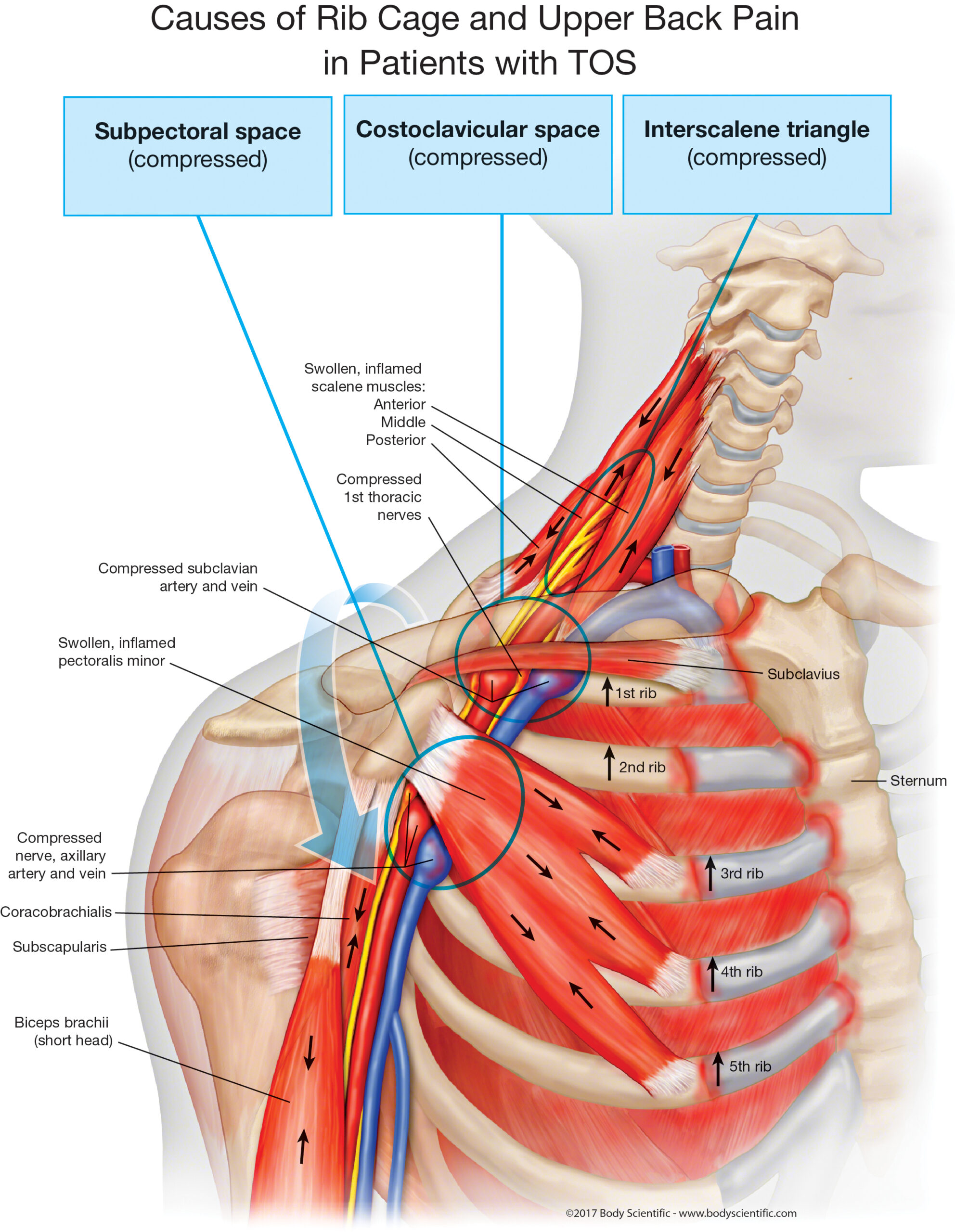

Patients often focus on the interscalene triangle, where the scalene muscles interact with the first rib.

Many individuals describe this area as the primary source of compression in Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.

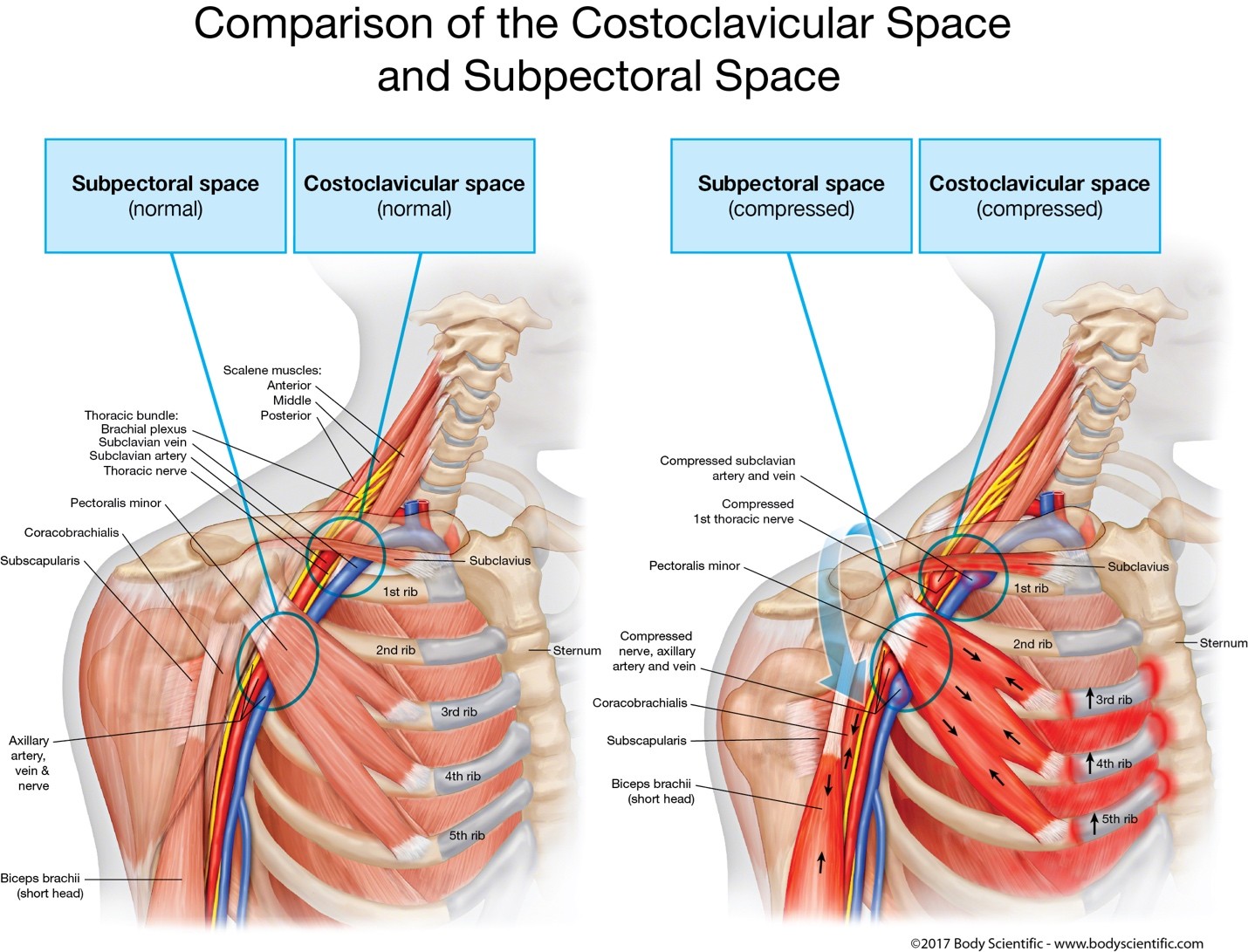

However, the anatomy is far more complex than what is commonly discussed. Few understand that the pectoralis minor muscle has the ability to lift the entire rib cage upward into the outlet, not just the first rib.

This upward force plays a major role in many patterns of TOS symptoms and contributes to cases where surgery provides little relief.

While vascular surgeons often consider elevation of the first rib and scalene spasm as the primary drivers of compression, the full picture involves multiple muscles acting together.

The chest muscles, especially the pectoralis minor, can elevate the rib cage from below while simultaneously pulling the shoulder downward into the thoracic outlet tunnel.

This creates a twisting and narrowing effect inside the upper body. In my clinical experience, this is one of the most overlooked causes of chronic neurogenic TOS and venous TOS.

This is also why many surgeries may fail.

If the entire rib cage is being lifted upward by the pectoralis minor, then removing only the first rib and cutting two muscles will not resolve the full compression.

Even when surgeons perform a pectoralis minor tenotomy, the coracobrachialis, subclavius, and biceps short head can still drag the shoulder downward.

This dual-directional force—rib cage rising and shoulder dropping—narrows the space for the subclavian vein.

Many individuals describe swelling of the arm, changes in color, coldness, and reduced grip strength due to altered blood flow.

When the rib cage rises into the outlet, the T1 nerve root becomes compressed at the base of the neck.

This often leads to tingling in the ring and pinky fingers, a hallmark of classic neurogenic TOS.

These symptoms arise not from a single structure, but from an entire upper body spring that is twisted by chronic muscular tension, guarding, and internal compression.

This is what makes the condition so difficult to understand without examining the full mechanical picture.

I personally commissioned a detailed anatomical diagram that shows how these forces interact.

It has since been published in medical journals by vascular surgeons in Italy and the United States.

They agree with this model because it accurately represents what happens inside the upper body during severe TOS.

The rib cage can elevate upward like a platform, and the shoulder can be dragged downward like a lever, creating a collapsing effect on the thoracic outlet tunnel.

Surgical removal of a single rib and two muscles rarely solves symptoms rooted in muscular compression.

Many individuals describe turning to surgery out of desperation when pain becomes overwhelming, believing that removing the first rib will relieve all symptoms.

But this specific procedure was initially designed for emergency blood clot cases such as Paget-Schroetter Syndrome, not for chronic muscular compression patterns.

If the entire upper body spring is twisted, elevated, and pulled downward by multiple chest muscles, surgery will not correct the underlying mechanics.

Understanding the true mechanical nature of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome allows individuals to see why some conventional approaches do not address the real source of compression.

The key is recognizing that TOS pain comes from severe muscle tension twisting the entire upper body, elevating the rib cage, compressing nerves, restricting blood flow, and creating long-term discomfort patterns.

In my clinical observations, chronic inflammation, splinting, and protective contraction can pull bones into positions where they do not belong, intensifying compression inside the outlet.

Surgery cannot unwind these patterns because surgery removes structures but does not address the spring mechanics of the upper body. Restoring the natural spring system—allowing the shoulder to suspend freely, the rib cage to move downward, and the chest muscles to release—creates space in the thoracic outlet tunnel that surgery cannot replicate.

When the upper body spring collapses, the shoulder no longer suspends properly from the rib cage. This alters the biomechanics of the brachial plexus, the subclavian artery, and the subclavian vein, leading to many of the symptoms associated with Thoracic Outlet Syndrome.

But when spring mechanics improve, the tunnel widens, circulation improves, and nerve tension decreases.

Ultimately, recognizing the interplay of the pectoralis minor, the rib cage, the shoulder complex, and the thoracic outlet tunnel provides the missing link in understanding why many individuals struggle with persistent symptoms.

Understanding this unified mechanical model allows people to see the true source of compression—and why restoring the spring is essential.

Team Doctors Resources

✓ Check out the Team Doctors Recovery Tools

The Vibeassage Sport and the Vibeassage Pro featuring the TDX3 soft-as-the-hand Biomimetic Applicator Pad

https://www.teamdoctors.com/

✓ Get Dr. Stoxen’s #1 International Bestselling Books

Learn how to understand, examine, and reverse your TOS—without surgery.

https://drstoxen.com/1-international-best-selling-author/

✓ Check out Team Doctors Online Courses

Step-by-step video lessons, demonstrations, and self-treatment strategies.

https://teamdoctorsacademy.com/

✓ Schedule a Free Phone Consultation With Dr. Stoxen

Speak directly with him so he can review your case and guide you on your next steps.

https://drstoxen.com/appointment/

#ThoracicOutletSyndrome #TOS #PectoralisMinor #RibCageElevation #ShoulderMechanics #BrachialPlexus #SubclavianVein #InternalCompression #MuscleGuarding #ScaleneMuscles #ThoracicOutletAnatomy #NeurogenicTOS #VenousTOS #UpperBodySpring #PosturalCompression #Inflammation #Vibeassage #TDX3 #TeamDoctors #ChestMuscles

References

[1] Sanders RJ, Hammond SL. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Review. Muscle Nerve.

[2] Hooper TL et al. Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: A Clinical Overview. J Man Manip Ther.

[3] Peek J, Vos CG. Functional Anatomy of the Thoracic Outlet. J Anat.

[4] Illig KA et al. Reporting Standards of Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. J Vasc Surg.

Dr James Stoxen DC., FSSEMM (hon) He is the president of Team Doctors®, Treatment and Training Center Chicago, one of the most recognized treatment centers in the world.

Dr Stoxen is a #1 International Bestselling Author of the book, The Human Spring Approach to Thoracic Outlet Syndrome. He has lectured at more than 20 medical conferences on his Human Spring Approach to Thoracic Outlet Syndrome and asked to publish his research on this approach to treating thoracic outlet syndrome in over 30 peer review medical journals.

He has been asked to submit his other research on the human spring approach to treatment, training and prevention in over 150 peer review medical journals. He serves as the Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Orthopedic Science and Research, Executive Editor or the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care, Chief Editor, Advances in Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Journal and editorial board for over 35 peer review medical journals.

He is a much sought-after speaker. He has given over 1000 live presentations and lectured at over 70 medical conferences to over 50,000 doctors in more than 20 countries. He has been invited to speak at over 300 medical conferences which includes invitations as the keynote speaker at over 50 medical conferences.

After his groundbreaking lecture on the Integrated Spring-Mass Model at the World Congress of Sports and Exercise Medicine he was presented with an Honorary Fellowship Award by a member of the royal family, the Sultan of Pahang, for his distinguished research and contributions to the advancement of Sports and Exercise Medicine on an International level. He was inducted into the National Fitness Hall of Fame in 2008 and the Personal Trainers Hall of Fame in 2012.

Dr Stoxen has a big reputation in the entertainment industry working as a doctor for over 150 tours of elite entertainers, caring for over 1000 top celebrity entertainers and their handlers. Anthony Field or the popular children’s entertainment group, The Wiggles, wrote a book, How I Got My Wiggle Back detailing his struggles with chronic pain and clinical depression he struggled with for years. Dr Stoxen is proud to be able to assist him.

Full Bio) Dr Stoxen can be reached directly at teamdoctors@aol.com